The Japanese Judicial System

1. The Japanese Judicial System

There are five types of ordinary courts in Japan: (1) Summary Courts, (2) Family Courts, (3) District Courts, (4) High Courts, and (5) The Supreme Court. Japan utilizes a three-tiered judicial system and, in most cases, a summary, family, or district court will be the court of first instance depending on the nature of the matter.

1.1. Summary Courts

The summary courts handle, in principle, civil lawsuits involving claims which do not exceed 1.4 million. The summary courts also handle civil conciliation cases and demands for payment. Furthermore, they handle criminal cases related to relatively minor offenses.are lawfully residing in Japan.

1.2. Family Courts

The family courts handle lawsuits related to personal status, adjudications and conciliations for family affairs cases, adjudications for juvenile cases, and other similar cases.

1.3. District Courts

The district courts handle the first instance of most types of civil, criminal, and administrative cases, as well as koso appeals against a final judgment of the first instance of civil cases rendered by summary courts. Most civil cases are normally deliberated by a single judge, except for cases for which the court has decided that it shall be tried by three judges, and certain other cases. Regarding criminal cases, generally a single judge handles a case, except for certain serious crimes which are tried by three judges. In Japan, the Saiban-in (lay judge) system, which will be described below, started in May 2009.

1.4. High Courts

The high courts mainly handle koso appeals, i.e. appeals filed against a final judgment rendered by a lower court, such as the first instance at a district court, a final judgment rendered by a family court, and the first instance of a criminal case at a summary court. In addition, on April 1, 2005 the Intellectual Property High Court, which specializes in intellectual property cases, was established as a special separate branch of the Tokyo High Court. or homeless.

1.5. The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is the highest and final court and handles appeals against judgments rendered by high courts (jokoku appeals) and certain special kokoku appeals that are prescribed under the procedural laws. It is composed of the Chief Justice and 14 Justices, with a Grand Bench comprised of all 15 Justices and three petty benches each comprised of 5 Justices. The cases are first assigned to one of the three petty benches, and those cases that involve constitutional questions are transferred to the Grand Bench for examination and adjudication.r homeless.

2. Judicial Proceedings

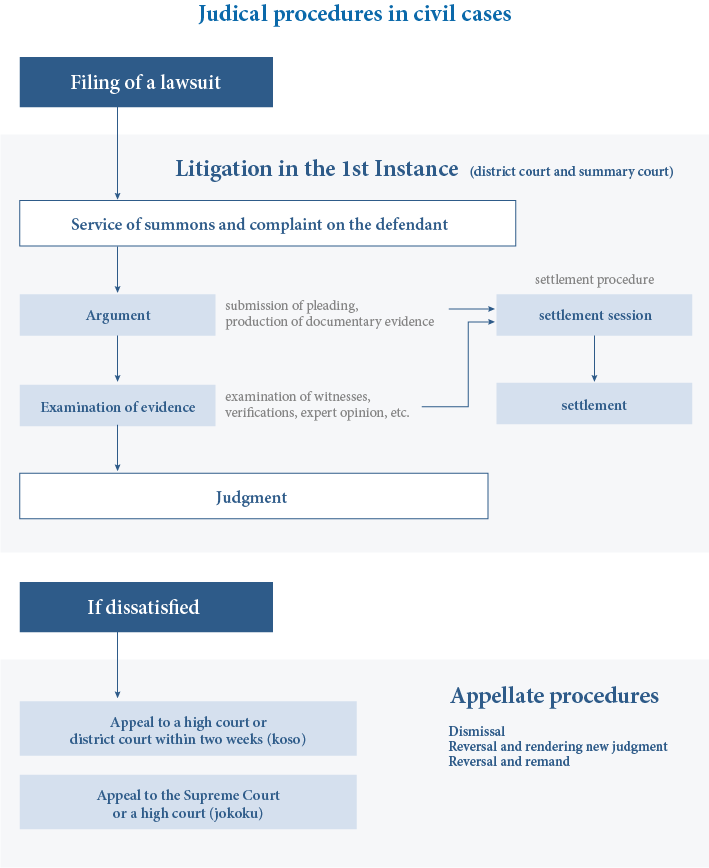

2.1. Civil Cases and Administrative Cases

Civil cases are legal disputes between private individuals. The classic examples are disputes over the lending of money or real property leases. Indeed, the vast majority of legal disputes are civil cases. When these cases are disputed in court, they are referred to as “civil lawsuits” in which an individual’s rights and obligations are ultimately determined by a judgment.

When an individual is not satisfied with a decision made by the central or local government, she or he may also seek a judgment from a court as administrative litigation, as well as file an appeal with the administrative agency. This category of cases is referred to as “administrative cases.” Examples include demands for the cancelation of taxes imposed by the tax authorities or nullification of an election.

The court of first instance for civil lawsuits is a district court or summary court, while it is a district court for administrative cases, with such courts judging the cases in accordance with the Code of Civil Procedure or the Administrative Case Litigation Act.

Labor cases are another important form of legal dispute. Regarding “individual labor disputes” between an employer and an employee, in April 2006, Japan introduced the Labor Adjudication System for individual labor dispute cases. Under this system, a Labor Adjudication Committee formed by a labor adjudicator who is a judge and two Labor Adjudicators who have specialized knowledge and experience on labor issues seeks to resolve the dispute generally in no more than three sessions by providing conciliation or adjudication. The objectives are to resolve cases quickly, appropriately, and effectively. Cases that cannot be resolved through this system are referred to ordinary judicial proceedings.

2.2. Family Affairs Cases

As their name suggests, family affairs cases are disputes involving the family, for example marriage annulments, cancelations, and divorces; custody over children; inheritance; and adult guardianship. In the resolution of family affairs, particular attention must be given to emotional conflicts and privacy considerations. Japan has applied a system of conciliation where family courts around the country dispose of many different types of family affairs cases with closed proceedings when the parties have difficulty resolving the cases themselves. Conciliation is conducted by a Conciliation Committee comprised of a judge or an attorney as a conciliation judge and members from the general public. If the case is not resolved by conciliation, it is settled through adjudication by a family court or through litigation. Whether the case is settled through adjudication or litigation depends on the facts of the case in question and the applicable laws.

2.3. Criminal Cases

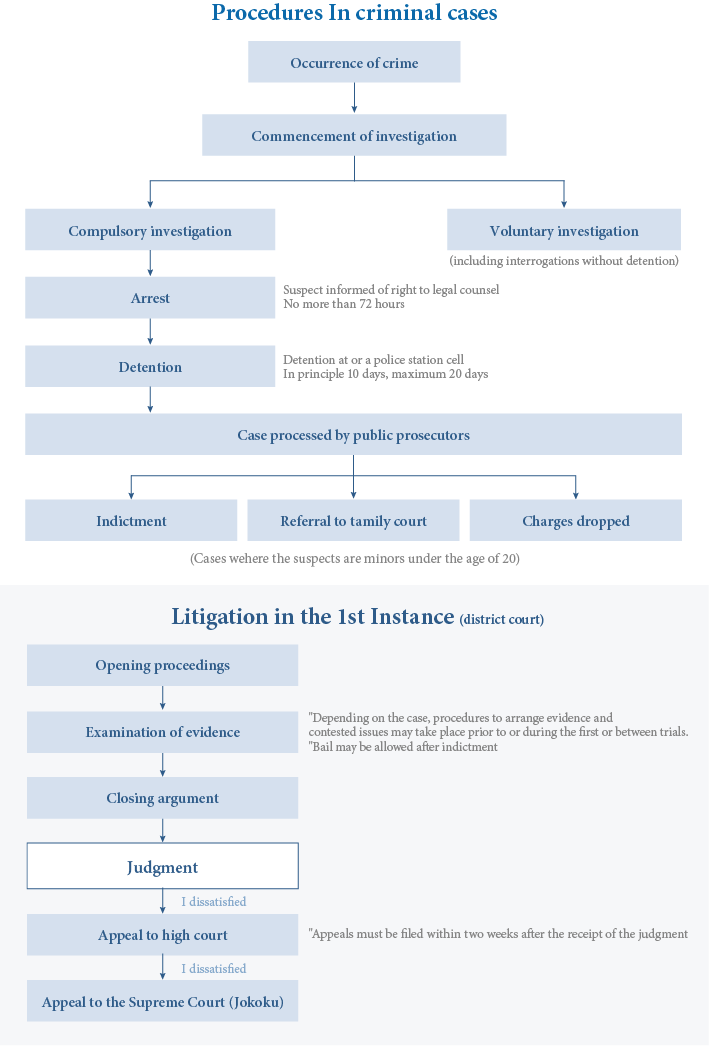

A. Criminal Procedure

Criminal procedure begins with the acknowledgement of the crime, and it proceeds to an investigation by the police and the prosecutor, indictment, and then to the trial.

One who is suspected of committing a crime (suspect) will be requested to appear in the police or public prosecutor’s office or arrested, and will be interrogated. Arrested suspects will be constrained in detention facilities of the police or detention center for up to seventy-two hours, and may be detained subsequently if necessary, for a period of ten days (up to twenty days if an extension of up to ten days is permitted). There is no pre-indictment bail system.

An interrogation is carried out in a closed room called an “interrogation room” in the police station or in the public prosecutor’s office. The suspect may be subject to many interrogations for a long time without the presence of an attorney.

By an amendment of the Code of Criminal Procedure in 2016, a system of audio/video recordings of the process of interrogations will be introduced by June 2019. However, the cases subject to this system are limited to the cases to be tried by lay judges and those in which public prosecutors conduct their own investigations. As a result, this system is not applicable to most of the cases.

Public prosecutors have the authority to indict the suspects. One who is suspected of committing a crime and indicted (the accused) will proceed to trial. If a suspect who has been detained prior to the indictment is indicted, the detention will continue after the indictment unless detention is canceled or bail is provided. The detention period is two months and may be extended for additional one-month periods in cases where it is especially necessary to continue the detention. The right of the suspect and the accused to have the assistance of competent counsel is guaranteed in the Constitution (Art. 34, and Art. 37, clause 3). A court-appointed attorney is assigned to suspects who are unable to retain counsel due to poverty or for other reasons. Previously in Japan, court-appointed attorneys had been assigned for defendants only after indictment. However, since October 2006, court-appointed attorneys are to be assigned prior to indictment for suspects of certain serious crimes who are detained. The scope of this court-appointed attorney system was expanded after May 2009 to include detained suspects of all “cases that require counsel in attendance in principle at the trial.” In other words, cases punishable with the death penalty, life imprisonment, or imprisonment with or without work for more than three years.

Furthermore, by amendment of the Code of Criminal Procedure in 2016, the scope will be expanded by June 2018 to include all cases where a detention warrant is issued to the suspect.

During trials, the main focus is on the examination of evidence. Procedures to arrange evidence and points of dispute may be held prior to trial or between hearings within a trial. When the cases are put into pretrial arrangement proceedings or inter-trial arrangement proceedings, public prosecutors are obliged to disclose evidence to a certain extent, but not in other cases.

Victims of certain serious crims and their bereaved family members can, if so decided by the court, attend hearings of the criminal trial, state their opinions, and interrogate the accused and witnesses, either on their own or by an attorney who has been entrusted by them.

For further information on problems in the criminal justice system and the JFBA's efforts toward the drastic reform of criminal procedures, please see “Reform of the Criminal Justice System”.

B. Saiban-in (Lay Judge) System

Under the Saiban-in (lay judge) system, lay judges who are randomly chosen from the electorate, serve alongside professional judges (six lay judges and three professional judges in principle) in examining cases in district courts involving certain serious crimes such as (i) any crime which is punishable by the death penalty, indefinite penal servitude, or imprisonment; or (ii) an intentional criminal act causing the death of a victim which is subject to examination by a panel of judges. The system was introduced in May 2009.

Lay judges participate in the hearing of the criminal trial with professional judges, conduct a public investigation of the evidence, and determine guilt and sentencing. Lay judges may ask questions to the accused and witnesses in the trial. The system is similar to a jury system in that lay judges are chosen at random from voter lists and appointed to serve on specific cases. It also resembles a lay judge system in that citizens participate in trials alongside professional judges.

It is believed that the lay judge system will actualize the principles of direct participation and of oral testimony in trials through things such as intensive court hearings convened every day, examination of the evidence in a way that is easy to understand with the focus on the testimony presented in court.

C. Retrial

The defendant has the right to file for a “retrial” after a guilty verdict has been finalized if new evidence is found, based on which a determination of innocence may be made.

2.4. Juvenile Cases

Juvenile cases are cases involving juveniles aged 14 to 19 who have committed a crime (juvenile offenders), and those cases concerning juveniles under 14 who have violated a criminal law or ordinance but are not considered offenders under the Penal Code because of their young age (juveniles who have committed illegal acts), and cases concerning juveniles under 20 who are likely to reoffend (pre-delinquents).

In order to realize the principles of the sound rearing of juveniles, articulated in Article 1 of the Juvenile Act, Japan has applied a system where every juvenile case is referred to a family court after an investigation has been conducted by the police or prosecutors. The family court investigates the accepted case and starts hearing proceedings. The hearing proceedings in juvenile cases differs from those in ordinary criminal cases. One difference is that juvenile hearing proceedings are not open to the public. Juvenile hearing proceedings may result in a decision of non-punishment or protective measures, such as probation or referral to juvenile training schools or children’s self-reliance support facilities. For cases in which the family court decides that juveniles should face criminal charges based on the results of an investigation, the family court may refer a case back to the public prosecutors with the decision of juvenile hearing proceedings for trial under ordinary criminal proceedings. In this case, the same criminal proceedings as those for an adult are conducted for the juvenile.

A juvenile may appoint an attorney as an “attendant,” however, the scope of the juvenile cases to which a publicly-funded attorney attendant can be provided is limited to certain cases for juveniles who are detained in juvenile detention centers, and the reality is that a publicly-funded attorney is provided only when the family court admits the necessity at its discretion.